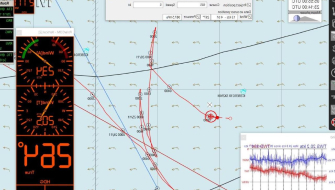

Engines on, motorsailing our way, gaining some west.

Westerlies abate, the seas calm down. It is just about 02:00h in the morning when we see the chance to break the loop where we ended up two days ago, wearing ship and heading north and south, to and from the ice edge and not being able to sail any westing.

Engines are turned on, square sails doused, headrig, staysails, and spanker sheeted tight. Our course bends towards the Antarctic Peninsula. We steer now west in the hope of getting around the pack ice. Steering south from our position has the risk of running foul of icebergs or getting fast in the pack ice, far away still from the Antarctic Peninsula.

The light breeze from the night turns up a northwesterly 20kn by the morning. But the seas are not growing, and the Europa can still make good progress. Even topsails are set, barely holding on, steering high in the wind. But not for long; they are set for about an hour until they have to be pulled down again. A process that is repeated several times along the day, depending on the variable winds that gradually back to a southerly and increase together with the swell, with the forecast to veer again to westerly soon.

Now on one tack, now on the other, headrig, lower staysails, and these topsails support the ship’s progress under engine. A journey too with any kind of weather; variable winds bring sleet, snow, fog at times, cold, and then sunshine, just to become overcast once more afterwards. On that way, plus some manoeuvring around bergy bits and growlers, we spent the day. But something else was to come; we were coming across something pretty cool to see in these waters, a truly Antarctic sight, a unique feature of these seas. First, it appears as a solid bar on the radar, then becomes visible as a line stretching through the misty horizon at our port side.

Low and long as it is, it doesn’t really look straight away like an iceberg. A second look reveals that actually, we are seeing one of the largest tabular icebergs that are drifting now off the Weddell Sea. It is about 30 to 50 meters high, flat-topped, and with reported dimensions of 40 by 32 nautical miles. Well over the 10-mile convention to be named.

It is the A23A.

After an iceberg of considerable proportions is sighted, the US National Ice Centre assigns a quadrant letter and a number based on its origin.

The large A23 is the 23rd iceberg followed in quadrant A (0 - 90 degrees W - Bellingshausen, Weddell Seas) since the beginning of tracking big bergs in 1976.

Icebergs of those dimensions split and crack into smaller pieces, which can get a suffix letter after their original denomination if they are over the threshold size to receive a name. For instance, A23A is the first fragment to calve from iceberg A23.

Further research to pinpoint the Weddell Sea ice shelf from where it originated tells us about the Filchner-Ronne one, and the year when it started its drifting: 1986.

Icebergs of those dimensions travelling out at sea with the winds and currents create their own mesoscale ecosystems. They interfere with the currents both on surface and in sub-surface waters, disturbing the general flow and often producing upwelling in rich waters. Moreover, they are loaded with mineral dust from the continent, affecting the nutrients for the phytoplankton in the local area. Attached to them travel microorganisms, microalgae, and small crustacean communities. All in all, forming a richer sea area around them which attracts birds and whales, as we could see today when we sailed just a handful of miles along it. Fin and Humpback whales blow here and there, flocks counting hundreds of prions fly around, and even a quite rare bird, truly a species from these southern latitudes, shows up — the Antarctic petrel.

For 38 years this tabular iceberg has been drifting from the southern depths of the Weddell Sea to be found now in the Scotia Sea.

From the Filchner-Ronne shelf to the open waters between South Georgia and Antarctica.

For the moment, it is in a destination which we know well, as we have been sailing already in the area for about five days. Not just this, but last year at mid-December, the Europa came across this very same iceberg not far from where it lays today, seemingly trapped in a conjunction of currents that don’t allow for much drifting.

On the other hand, its area of origin, deep into the Weddell, hasn’t seen many visitors. The ice shelf there is divided into two areas: the eastern (Filchner) and the larger western (Ronne). Combined, they represent the second largest ice shelf on Earth, after the Ross Sea one.

Commander Finn Ronne, leader of the Ronne Antarctic Research Expedition in 1947–48, discovered, flew over, and photographed this western part of it. But it was much earlier when the first portion of the ice shelf was found. The eastern part of the Weddell was first trodden by the human foot during the German scientific expedition led by Wilhelm Filchner on board the ship “Deutschland” in 1911. A research enterprise with several goals, from oceanography to geology, and the idea to determine whether West and East Antarctic were connected by land or ice.

For that, they steered the ship to the unknown coast far east in the Weddell Sea. The original plans of their quest suffered unfortunate and unpredicted circumstances, some to be solved at South Georgia with the help of Carl Anton Larsen (a name that we know now well and has come up several times during our present trip), others further south into the icy seas. The drawbacks, misadventures, and hassles included an unplanned overwintering beset in the ice, sabotage, and a crew at the brink of mutiny.

Back in Germany, and surely because of these troubles, the expedition never got the credit it deserved for their discoveries. Important findings which include: the southernmost latitude achieved at the time, the mapping of new lands, the finding of the nowadays called Filchner-Ronne ice shelf, and the description of the Antarctic Convergence, with the change of salinity and temperature of the waters surrounding the Antarctic Continent.