Drake Passage

Light winds and good weather in the morning, becoming cloudy and rainy later on. Wind picks up in the afternoon and evening, with good sailing starting in the night.

A night of twilight, complete darkness never takes over it, in the summer on the High Latitudes of the Southern Hemisphere. And it will just get lighter and lighter as the days pass by, and we find ourselves further and further south. A situation that helps to actually see what we are doing on busy nights on deck, like the one we had yesterday, and the one that was to come today.

In the early hours of the day, a squall hits first, then a light wind blowing from where we want to go, an unfavourable situation for sailing, which means we have to use the ship’s motors. Trying to make way under sail resulted in bending our course eastwards, drifting under the breeze and leeway current, but not achieving any progress towards Antarctica.

We are carried under those circumstances by the surface ocean circulation, the Cape Horn Current, which flows from the Pacific rounds The Horn and flows then on an easterly, northeasterly direction. Slightly south, the upper limit of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current flows too from the west.

With her engines working and her Lower Staysails, the Europa pushes her way southwards against the wind. A breeze that later on veers to a more Southwesterly direction. Now, Top gallants, Courses, and outer Jib can be set again, since they were doused during strong gusts blowing for a while and before the wind shifted to a southerly. In that fashion, we try to combine sailing and Motorsailing for a while, but not for very long, the sails don’t hold well under the circumstances of a calm Drake where just a gentle long swell rocks the ship, and light winds with a southerly component.

That means it is time again for clewing up all the squares. Now we make way under engine, Lower Staysails, but Desmond, headrig, and Spanker.

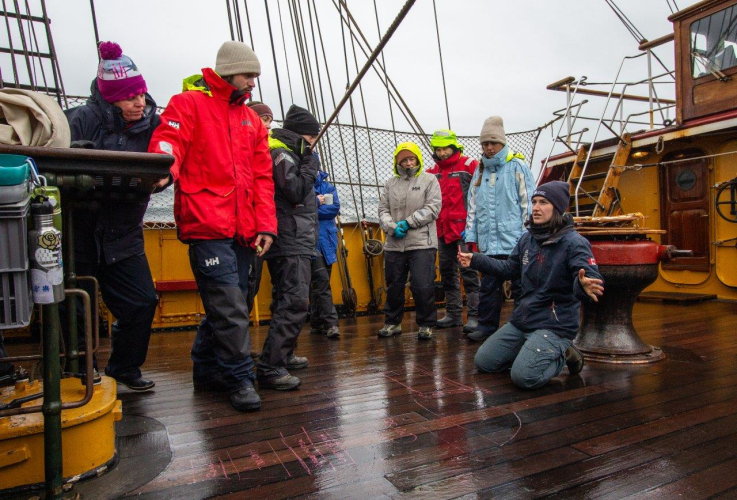

Calm as this passage can be, sun shining in the morning and all, unavoidably, sea sickness strikes some. Yesterday evening, the watch system started, today the three voyage crew watches have experienced some thinning, with a few staying in their bunks or just having to hang around in the deck’s fresh air. The rest participates in the steering, lookouts, and even a few climb aloft to help furling some of the sails and show up for the first sail-training and lectures of the trip.

Calm as this passage can be, sun shining in the morning and all, unavoidably, sea sickness strikes some. Yesterday evening, the watch system started, today the three voyage crew watches have experienced some thinning, with a few staying in their bunks or just having to hang around in the deck’s fresh air. The rest participates in the steering, lookouts, and even a few climb aloft to help furling some of the sails and show up for the first sail-training and lectures of the trip.

On our horizon, the Antarctic Peninsula, but before we have to face the latitudes of the so-called Furious 50’s until reaching the Screeching 60’s, both adjectives give an idea of the difficulties of this crossing. So far, the conditions are still good, not really for the actual sailing, as the winds are light, but the seas are not rough, with a ship gently rolling in the long, low swell. Here it can easily grow as it travels along the uninterrupted waters that flow around the world at those southern high latitudes.

But of course, this is the Drake, it wouldn’t be such a famous crossing if its temper and variability didn’t show up.

The moody waters of the southernmost connection between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, a passage that had to wait until 1578 to be found, when the extension southwards of South America and the existence of a hypothetical Southern Continent was unknown. By then, as many others before and after, the unpredictable weather and large low-pressure systems constantly sweeping over the area blew off course the sailing ship Golden Hind under the command of the privateer Sir Francis Drake. Instead of a smooth passage through the Strait of Magellan as intended, they were first pushed southwards, sighting the southernmost tip of the Americas and the waters extending south beyond it. Since then, this oceanic stretch of approximately 450nm bears his name.

The 6th day of September we entered the South Sea at the cape or head ashore.The 7th day we were driven by a great storm from the entering into the South Sea, 200 leagues and odd in longitude and one degree to the southward of the Strait.

…

From the bay which we called the Bay of Severing Friends, we were driven back to the southward of the Straits in 57 degrees and a tierce.

Francis Pretty. Crewmen on Drake’s circumnavigation of the world. Account of the historic voyage published in 1910.

They found that Tierra del Fuego was an archipelago, described like this during the trip: “In passing along we plainly discovered that same Terra Australis to be no continent, but broken islands and large passages amongst them…”. The Pacific and the Atlantic oceans met, and it should be possible to sail ships around the bottom of South America. The Cape Horn route eventually sailed first in 1616 by the Dutch merchants Schouten and Le Maire.

And so, the distinctive, changeable and often rough weather that characterises these seas hit us. In the evening, the seas grow, and the wind keeps increasing, reaching a strong Southwesterly with peaks up to the 40kn. A new situation that makes for a busy night, when hands are called on deck for first bracing sharp on Starboard Tack, then start sail handling. Topsails are set over the main deck, the small Aap is hoisted, and the Outer Jib is packed away just before the strongest gusts blow. Now we sail, the engines are turned off. Both Top Gallants are readied too, but just the Fore one is sheeted down, and its yard pulled up, but not for long. It is before midnight when they are furled again. Since then, the sail configuration seems to be the most appropriate to work with for the rest of the night.